Shaping health information systems for data-driven decision making

In this interview, Dr. John Lewis shares experiences from his work with HISP in Mozambique, South Africa, India, Lao and Vietnam, recalling the process of establishing new HISP groups and developing early versions of the DHIS2 software.

This interview is part of a series of articles on HISP history and impact, published as part of a yearlong celebration of the 30th anniversary of HISP.

When did you start your journey with HISP and DHIS2?

I started with HISP in the year 2000, working for the Indian Institute of Management (IIM) in Bangalore, where I was a software developer for HISP in India—there was no official HISP India group yet, so it was just like a small research project with the University of Oslo and the IIM Bangalore.

I was hired to customize the DHIS1.1 to the local setting, because I had programming knowledge. The focus at that time was only aggregate data within the HMIS, and all of the data reporting forms from the various programs, which the health centers were reporting to the higher level. I was focused on one constituency with nine health care centers, and I actually stayed there in one of the centers for three months to understand their work routines, how they collect data, how they aggregate data—and all these things were paper-based. There was one computer installed in each center, but no internet access. The idea was just to see how best we can try to reduce the healthcare workers’ aggregation time, based on all the things they were supposed to report. Additionally, we wanted to make a kind of standard report—which was not available in DHIS1—we planned to make it in Excel so they could generate and view their target and achievement. That was in Kuppem, which is in another province, where they spoke a completely different language. I didn’t know their language, and the script is completely different, so I was also learning the language as I was working to build the system there.

At that time, DHIS1 had two parts—one was data collection and one was the data mart—as two different databases. There were no other developers with HISP in India, so it was just me. All of the DHIS1 development had been done in South Africa, and they had a different approach to standard reports, preferring to have facilities or ministries creating their own reports. In India, they wanted someone who could create reports to be exactly in the same format, and they wanted the charts and graphs to look a certain way, rather than having people make these by themselves. So what I did was use a visual basic plugin, which can talk to DHIS1 and generate all the reports and the charts and graphs that they wanted to monitor, so that health workers can actually use the data.

When I started my master’s degree with UiO in 2002, I was doing work in Andra Pradesh state in India. There, we had been trying to include the standard report as well, but also including geographic information system (GIS) tools like map objects. My master’s was on GIS, and how we could try to use GIS for community health, and I created an app called HISP Spatial Analyst as part of that effort to build up the reporting capability.

My master’s program was six months in Oslo and then the remaining one and a half years in Mozambique. When I went to Mozambique, I was customizing the Indian Spatial Analyst to the Mozambique context, so it could actually talk to the DHIS1.2 data mart file, and then the spatial object to generate all the DHIS2 data to the map rendering. During this time, I went to Cape Town and worked with Calle Hedberg, trying to build up all the different things to be added to DHIS1.4, especially the concept of the groups, like org unit groups and others. That was a team effort between me, Ola Titlestad, Zeferino Saugene, and a master’s student from the University of Oslo, at that point, and it was made available to the wider community in a later version of the software.

Then, DHIS1.4 was released, which had been talked about for quite some time. It took 1-2 years to release because there were lots of things being added on. It wasn’t just me—the whole master’s student cohort of eight or nine people, plus several others, worked together on this. After the work was done, I stayed behind to work with Calle a bit longer, so I could take the CD back to India. That’s how it worked at the time—if there were updates, Calle would burn the new software to a CD, and we would take that to India, and use it to implement in different health centers one at a time.

DHIS1.4 was implemented in many of the health facilities in India, at the district level. When we moved to the Kerala state level in 2005, we were then implementing DHIS2. That year, we also started using DHIS2 in Kerala, while transitioning from an earlier version to DHIS, trying to convert all of the system functionality into the new Java-based system, but in a local deployment that could work in offline mode, since internet coverage was not yet good enough there to run it online. One of the UiO master’s students was the pioneer in this effort, and started configuring the DHIS2 model, which was tested in this one state in India.

How did the software eventually transition to the web-based solution?

We had waited such a long time to move to the web-based system, because access was limited and the data was growing more and more—we could not support most of the activities. We wanted to go to the Java-based system, and we had a couple of good programmers in India, so they tried to create something with the exact same functionality, based on their knowledge, in a web-based system. The first time we were presenting DHIS2 in front of the whole university, the demo didn’t work, so we used the alternate one that the Indian programmers had developed, to keep the crowd interested, because there were a couple of very critical bugs that we couldn’t resolve at the moment. A master’s student, Christian, was on stage in front of an audience, and we had to do something, so we asked our colleagues to get the software running. It was basically the same—the UI looked exactly the same, but the back end was different. That’s essentially when it started. When we tried to implement DHIS2 in other states—and with other states in India, it’s like another country because of the different political structure and other things. Also, internet access was not available, so we used to install DHIS2 servers in each health facility as a solution for the lack of web access. There was one person who would go around to every health facility, download the database, come back to the district and upload that to the central server. So, that was how DHIS2 started when there was no actual internet at the health centers. It was in 2008-2009 that internet access came all the way to the health center, so people could use the online system to report. That access also created a new challenge, because at that time, we had hundreds of employees—there were 60 in Jharkhand, 4 in Madhya Pradesh, 20 in Andhra Pradesh—because everyone had to go around and install updates, etc. For every district, we had one person appointed, and we taught them how to use DHIS2.

How did DHIS2 change things at the district level, at that time?

In India, every province is like a country—in Andhra Pradesh at that time, there were 75 million people. To make sure their voices were heard, we brought in some of the province health workers and explained how DHIS2 could help them. I remember, there was an older health worker who brought the whole patient register, the big log book, and said “I’m 68 years old, this takes me like 7 days to report, but now with DHIS2, I can do all of this within one hour, so I have more time for my patients, and for my family. These books are very hard for me to carry.” That was an eye opener for me. The higher level people were making these bulky books, which were very hard for health workers to carry, and the same thing happened in other districts as well. Workers had to cross a river, which meant they had to carry the books on their heads to keep them dry. So DHIS2 helped them in that way, and reduced their workload on calculation, aggregation, and reporting, which was really major because every health worker had one of these big register books, and maybe different village books based on local health programs, and they were typically reporting the same data again and again in different places.

How did this change data use in India?

The big outcome happened later in 2008, because at that time all health centers and smaller sub-centers (which are below what are commonly called health posts in other places) were supposed to report on 3,500 data elements monthly. Based on our comparison of five different states, we found that 95% of those fields were blank. We were actually finding data quality problems, data entry mistakes, etc. With this information, we made a few key changes, and this was supported by the national-level system NHSRC, the National Health System Resource Center, where we presented this data to the Health Secretary of India, saying we need to reduce these data elements. Before, all of the fields were disaggregated by age, gender, and ethnicity, and that created enormous problems for reporting. We introduced the five key principles, and with only the first two—no duplicate reporting, and no disaggregation that is not useful at action level—we reduced many of those fields. After this reform, those 3,500 fields were reduced to only 65 for the health posts, 135 for primary health care centers, and 170 for hospitals. That was not a direct data use in itself, but the ability to solve the data quality problem to make the data usable for local action. That was the biggest achievement, not not directly from DHIS2, but using DHIS2 as a means to show much much blank reporting was happening in these provinces.

How did your work with HISP expand beyond India?

After working with DHIS2 in India for several years, I moved from India to Vietnam, trying to set up HISP Vietnam, and had to do all the same things all over again. I started working on implementation, and the first country we tried to work with apart from Vietnam was Lao, in 2013.

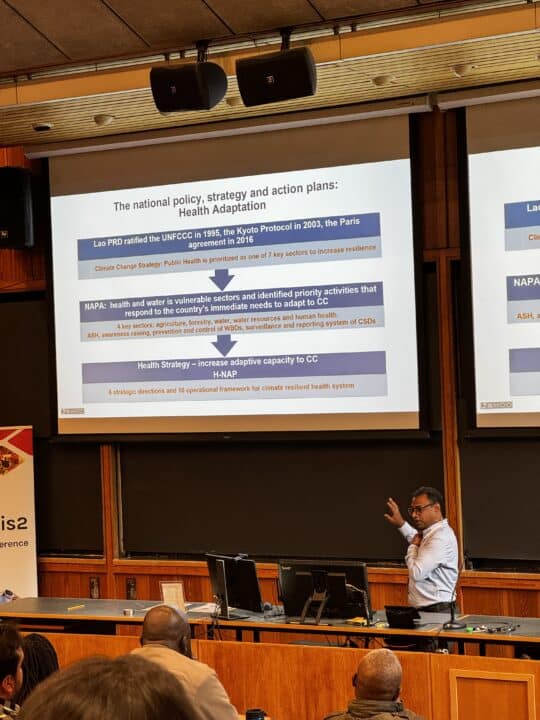

When we started in Lao, one of the good things was they didn’t have any systems. The only data they collected was in Excel. But one of the challenges was, there were development partners that were supporting individual provinces—at that time, there were 17 provinces, now there are 18—but no one was supporting the HMIS yet. With the WHO and the Department of Planning and Finance (DPF), we worked to get all the development partners together and we presented DHIS2 and explained how it could help them manage a national database, and that the country needed a more sustainable and cost-friendly way of implementing. We tried to unify all of the development partners, to put all the money into health system strengthening, to get donors to support a central solution. We started with the HMIS program to collect aggregate data, and then we tried to import the existing data from their Excel system into DHIS2 so that we could show the national coverage. The WHO and DPF talked with the cabinet, so the Health Minister was there during the first review meeting, so we had high-level collaboration and support.

In 2015, DHIS2 was rolled out nationwide to collect aggregate data from all the health centers, but not all centers were entering data because they lacked internet connection. Those centers sent paper forms to the district to be entered for them. Later on, we worked on the offline module so the health workers could enter the data on their laptops and they could upload it when they went to a district meeting, for example. The World Bank and The Global Fund had already supplied laptops to some of the facilities, so we created an offline, desktop-based app so they could report using their own devices, which reduced effort and cost for buying devices.

Then, since it was just aggregate data, we reached out to the health center, and tried to create national, provincial and district core teams, which were officially endorsed by DPF. The national core team had members from different programs—some from immunizations, some from malaria, some from HIV, TB, etc.— and they combined together to create a national core team. Lao is a low-resource country, so we needed to combine the workforce in that way for better, less expensive results, rather than a siloed system. We had help from the cabinet, the secretary, and the Health Minister, to change the terminology for the various units and combine all programs into a Provincial Health Office. At the district, it was the District Health Office, DHO, so everyone had to think through how to work together in one district. Additionally, we created a set of rules for which department was responsible for which things—DPF would handle the health facilities, but anything related to the individual programs would be handled by the program itself. DPF had access to the back-end DHIS2, and they would be responsible for changing a facility name, updating those fields, etc. Because everything was housed on one server, and DPF was responsible for the maintenance, security, and backups, this helped eliminate extra expenses associated with separate systems.

When we started HISP in Lao, we knew Lao and Vietnamese were such different languages. Some Lao people understand Vietnamese, but no Vietnamese people will understand Lao. We were very fortunate to have people who knew Lao, and who had been working with the WHO, and they joined with HISP Vietnam to work for the country. We first trained some of those people and sent them to work inside the MoH, like in the DPF. But the DPF didn’t really have the manpower or resources to sustain them, so that strategy didn’t really work. What we are doing now, which is working quite well, is establishing a HISP Vietnam branch office in Lao. We have hired people from Lao, who worked previously in the WHO Lao country office using DHIS2. Currently, the HISP Vietnam team in Lao works closely with the DPF and other stakeholders to understand their needs, and support MoH in managing, maintaining, and sustaining their DHIS2 systems.

How have you supported local innovation and adaptation to new challenges/needs?

We’ve been having developer workshops in Lao, where we are teaching them how to make apps. So they’ve been making apps, line lists, event reports, and things like that. These are different things we’ve shared with UiO developers, which they’ve embedded into the core DHIS2 line listing app. Local innovation is still happening, as well. We’ve been trying to use our dev resources to understand how to best support or use the data for their particular program, and establish procedures that local partners can use to add their own innovations in a standardized way. We have three development servers set up only for Lao. They do development there, and then when the apps are approved, they are sent to HISP Vietnam for review, before being installed on the production servers.

How do you engage with the DHIS2 core team, the HISP network, and the larger DHIS2 community?

For me, being with the HISP network is just like built-in, since I’m one of the oldest members. I don’t think we have many people who have been around this long, since the beginning with DHIS1. Our thinking has always been linked with the UiO global initiative. What we’re trying to do now is strengthen the HISP Asia network to facilitate others to communicate with UiO and the global network. For me, it’s not a problem to communicate with HISP UiO or others, but how do I enable other HISP members and HISP groups to communicate with the global network. One of the biggest challenges in the Asia region is the language and the shyness to communicate with the global team. It’s very hard for people to talk to you if they don’t actually know you. Usually they would talk to their supervisors and immediate team members, but that’s a cultural difference between the west and the east. One of the things I’m trying to solve now is the communication gap between HISP Asia team members and HISP UiO. Even within the HISP Asia region, members aren’t always comfortable communicating with each other. We are beginning to see positive results in this area, because of the HISP Asia conference where people can meet in person, which then encourages further communication.

How would you describe and/or quantify your HISP group’s success/impact?

The impact of a HISP group always depends on the implementation and what you try to create. We always try to make a bridge between global and regional partners, the Ministry of Health and the country development partners. That’s where HISP plays an important role, because HISP has knowledge about what is happening at the local level, the regional level and the country level, and most people in these organizations don’t have that knowledge. We want to bring new global initiatives to the country quickly, tailored to local needs, and we want to share where you can actually find the resources—sometimes those resources may not be in my HISP group, but in HISP Sri Lanka or others, or other partners—and this happens through the collaboration with UiO and the regional partners. That’s where we make the biggest impact to the MoH, helping them to choose the right system, helping with implementing the right product, and focusing on data use for action.

I have one famous quote, from the director of DPF, several years ago. “Lao is one country, one rule, one DHIS2.” All data has to go through DHIS2. HISP is a network where we have a long-term relationship with all people, we work on trust, deliver trust, maintain trust. We do whatever is best for that particular country. That’s our strength.

Learn more about how the HISP Centre and the HISP groups collaborate to support countries worldwide on the HISP network webpage.