The DHIS2 Annual Conference takes place from 15-18 June 2026! Learn more

HISP Tanzania: Advancing Digital Innovations to Empower Information for Action

In this interview, Dr. Wilfred Senyoni discusses Tanzania’s journey with DHIS2, and how HISP Tanzania has developed into a leading partner for innovation and capacity building

This interview is part of a series of articles on HISP history and impact, published as part of a yearlong celebration of the 30th anniversary of HISP

What is the history of DHIS2 and HISP in your country?

Wilfred Senyoni: The history goes way back. It started in the 1990s, when Jørn Braa was doing his PhD studies that led to the development of DHIS v1. He initially had planned to include Tanzania as one of his case studies. It didn’t pan out at that time, but he remained interested, and later on we were able to start a collaboration between the University of Oslo (UiO) and the University of Dar es Salaam (UDSM). We exchanged students between the two universities, and this helped set up a pilot of DHIS v1.4 in two districts in Tanzania: Bagamoyo and Kibaha.

The reason we were setting up this pilot was because at that time Tanzania had a Health Management Information System (HMIS) that was largely paper-based, and which had a lot of challenges. It was not sufficient for the Ministry of Health’s needs, was not very flexible, and there was little local capacity to support it – any changes required us to bring in international consultants. So piloting DHIS v1.4 was quite useful. The success of this pilot and the decision by the MoH that Tanzania needed an integrated HMIS that included both paper and digital tools led to a revolutionary change in 2007 with the formation of the MESI (Monitoring and Evaluation Strengthening Initiative) consortium. This consortium included UiO, UDSM, and the MoH. Our work involved updating the paper HMIS tools and the selection of DHIS2 as the main HMIS software for Tanzania.

We started piloting DHIS2 in Pwani region in 2011. In 2012, this grew to five regions, and by 2013 we had scaled DHIS2 to cover the entire mainland. That’s how DHIS2 got started and scaled nationally in Tanzania. It was a huge collaboration between the MoH, UiO and UDSM. I was the project manager at UDSM coordinating these activities, ensuring that we followed the plan and managing different financial and technical partners like the Global Fund, Norad, UiO, the Dutch Embassy, and other stakeholders.

At that time, we were working as part of the technical working group at the MoH responsible for M&E and ICT. As DHIS2 started getting more attention as a central HIS system, there was a need to create an institution that could respond to the increasing demands. We had already started to refer to ourselves informally as HISP Tanzania, but we were still part of the UDSM organization. UDSM is primarily focused on research and teaching work, and we realized that we needed to start a more flexible and agile organization that could focus on addressing local and global needs and challenges, building expertise and innovation with digital tools, and following global standards and practices. In 2016, we formally instituted HISP Tanzania. The founding team was myself, Ismail Koleleni, Masoud Mahundi, Honest Kimaro, and Bernard Mussa. Since then, we have expanded to support not only the Tanzania mainland, but also Ministries of Health in Zanzibar, South Sudan, Eritrea and all three states of Somalia, and have gone from working with one partner to multiple partners internationally.

How did your own PhD studies fit in with your DHIS2 and HISP work?

As we were implementing DHIS2 in Tanzania, there was an opportunity to support regional efforts in the East African Community (EAC). Norad gave funding to UiO and the EAC to develop a regional system to support Maternal and Child Health (MCH) and cross-border disease surveillance programs in the EAC region that could interact with national HMIS systems. We started that project in 2014. We worked with UiO and the EAC team to conduct an assessment of the EAC countries and design a regional system, which was one of the earliest regional DHIS2 platforms, along with WAHO in West Africa.

During this work, from 2014 to 2016, we found that there was a real need for using standards in national systems, because the metadata in different countries did not always align. So a large part of this project was working on standardizing key indicators. A good example is in MCH, where in Tanzania were monitoring an indicator like postnatal care within two days of delivery, while in Kenya they were doing it within seven days. Another example is delivery. Some countries were monitoring delivery by skilled attendants, while another country might be only monitoring delivery in health facilities. When you are comparing across multiple countries you need common standards.

This inspired me to start my PhD (in 2016) focusing on the question of how do we establish standards to help integrate multiple systems so that key information can be available for decision makers to use. As part of my PhD research, I was also able to travel to Indonesia to see how these fragmentation challenges and standards work in a different country and context, where districts and provinces could have their own information systems. This helped me see how this problem of standardization can apply at both the country and regional levels.

I completed my PhD in 2021. One of the significant contributions of my research to HISP Tanzania’s work was this focus on standardization. For example, when we began developing the EAC regional scorecard, there was a clear need for standardization to make useful information available to decision makers.

What was the impact of your work with scorecards?

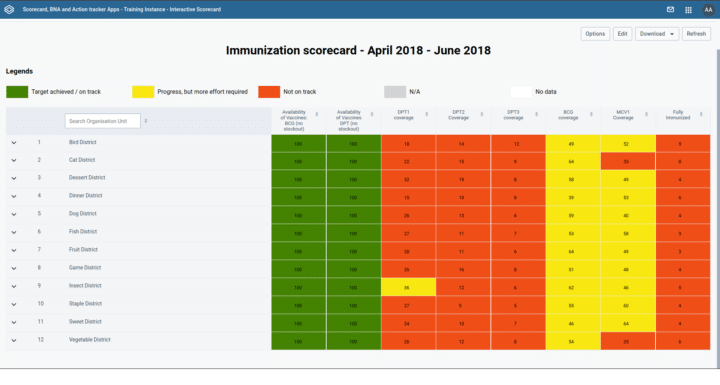

First, let me explain what a scorecard is. The scorecard is a visualization tool for monitoring key indicators. It uses a traffic light analogy, where red means there is a problem, yellow means there is some progress, and green means the target has been achieved. The idea with the scorecard is that you don’t need to put all of your indicators or information there. It’s more to make it easier to monitor the key, strategic indicators to help understand your progress. And the good thing about this “traffic light” design is that you don’t need to be a public health expert to understand the indicator status. Everyone understands that red is bad and green is good. The scorecard in DHIS2 has been a very effective tool to communicate performance to decision makers, especially political leaders, so that they can see where the gaps are and allocate resources to address them.

A good example is the first scorecard we launched in Tanzania, which was for MCH. This scorecard went to the district level and had multiple indicators including pre-pregnancy, delivery and postnatal outcomes. One of the key indicators was maternal mortality rate, and the scorecard showed that some regions in Tanzania were not performing well. This stimulated action from political leaders, including follow-up down to the facility level. As a result, we have seen significant improvement in maternal mortality indicators across the EAC region, with Rwanda leading the pack. Nowadays, whenever a maternal death occurs, there is an audit to try to understand why the death happened and if it could have been mitigated. Through these interventions, maternal deaths due to negligence as well as infant mortality have decreased.

The scorecard initiative has really gained momentum at both the EAC regional level and the national level. For example, Burundi requested support from us to implement a national-level scorecard. When we went to implement it, we also advocated for standardization of the data they were collecting and for using the scorecard to make the data easily accessible to decision makers. We did similar work in Zanzibar. At the regional level, we have been supporting the technical implementation and providing support to the team on how they can analyze their data. For example, just this month we met with the EAC to discuss how they can publish their regional scorecard for 2023. And in Tanzania, we have also helped extend the use of the scorecard to the subnational level. Overall, this project has helped the EAC and countries to standardize, view, and use their data.

How does this work exemplify the HISP approach?

The scorecard is a good example of how we can go from a local innovation that supports a specific need to a generic solution that is shared globally. The scorecard project started in 2011 with ALMA (the African Leaders Malaria Alliance), which was focused on reducing malaria and wanted a mechanism for visualizing and monitoring performance. ALMA came up with the “traffic light” scorecard design around 2012. In Tanzania, we adopted the same idea and adapted it for MCH in 2013. At that time, we were developing the scorecard outside of DHIS2, but we realized that most of the data was coming from DHIS2. We decided we needed a mechanism to create this scorecard within DHIS2 so that it was available not only to national-level stakeholders, but also to the health workers who are providing services so that they could measure their own performance.

In 2014, we started developing an html version of the scorecard in DHIS2 to allow users to generate the scorecard and visualize the data. HISP Uganda had also started doing similar work for MoH Uganda around the same time. In 2016, there was a need to streamline these efforts and enhance collaboration between groups, so we got funding from UNICEF to develop a DHIS2 scorecard application and enhance use of scorecard analysis. We worked with HISP Uganda to collect and analyze the requirements, and develop an app that standardized the way people collect and use the scorecard data. This project was a cornerstone for HISP Tanzania’s development as a group, because it enabled us to form a collaboration with HISP Uganda and to work more closely with the UiO development team and understand their process and standards. Together, we were able to develop an app that meets the demands of users, stakeholders, and the HISP network, and which is now available to the entire DHIS2 community through the App Hub.

The knowledge and experience we have gained through the scorecard project has also helped HISP Tanzania to develop our skills and reputation for DHIS2 app development. We’re now regarded as one of the HISP groups that develops key applications that can be used across the network. I’m proud to say that we have won the DHIS2 App Competition at the Annual Conference for two years in a row. We’ve also seen that some of the features we developed in the scorecard application have been adopted into the core DHIS2 software, which is a good indication that our work has been useful to a wide audience.

The scorecard project has also led to additional innovations in data analysis and use, such as Bottleneck Analysis (BNA), which helps determine the root causes of underperforming indicators on the scorecard – the scorecard shows you the problem, while BNA helps you understand what to do about it. A related innovation is the Action Tracker, which helps track specific actions to improve indicator performance. These innovations and opportunities have come through our successful implementation of the Scorecard app and how it has gained momentum across countries and across the HISP network, supporting data analysis and use. In Tanzania, UNICEF has piloted the BNA app in several districts, where it has helped health teams identify specific problems and plan and budget actions to remedy them. One good example is from a district team that determined that poor indicator performance for service delivery was actually due to stock-outs at a particular facility. With the BNA app, we could drill down to see not only about the performance issue, but what was causing it.

How have you supported sustainable information systems, including with tools beyond DHIS2?

Sustainable information systems have been a focal point of our approach since the beginning. The prior HMIS in Tanzania was not sustainable or flexible. When we changed the approach and introduced DHIS2, we were thinking about how we can implement information systems that will be sustainable. A big part of this has been a consortium approach, in which the MoH drives the process and where we have political will to implement and support the system for the long run. It has been critical to engage multiple stakeholders, with the MoH in the front and our team being the technical arm, being innovative while also making sure that any innovations we introduce are open-source and follow the MoH’s plan.

We have also supported architecture and integration. DHIS2 is our bread and butter, but DHIS2 cannot be used for all systems in the health domain, so we have been working with MoH to ensure that data from other systems can be viewed in the HMIS. A recent report assessing Tanzania’s health information systems indicated that there is a proliferation of digital tools – such as logistics and lab systems, for example – so we are working with the MoH to integrate these systems and ensure that the data flows between them. The TimR immunization register is a good example. We have been working to integrate this system with DHIS2 so that the data managers can easily access their data for a comprehensive view of immunization and child health indicators. Promoting integration and interoperability across the systems for visibility of data is a key part of supporting sustainable and effective systems.

How has your HISP group helped strengthen local capacity?

Capacity building has always been a cornerstone of HISP Tanzania. The first DHIS2 Academy ever was hosted in Tanzania back in 2011. At least a dozen countries came to attend. Since then, we have supported countries through these regional academies, working with other HISP groups in the region to build capacity in the region in different areas. We have also worked with UiO to host more specialized courses such as the Community Health Information Systems (CHIS) Academy we hosted in Dar es Salaam in 2023 for more than 60 participants. In addition, we have supported national and subnational training in mainland Tanzania and Zanzibar, and we have provided training and mentorship to the other countries we support, both by traveling there to conduct trainings and by bringing people from their national teams in Tanzania to learn specialized skills like server administration and maintenance. For example, we recently hosted technical teams from Somalia and South Sudan for multiple weeks of in-depth training and mentorship.

Several members of HISP Tanzania, myself included, also have positions at UDSM as lecturers. I currently lead a postgraduate program there for data science students with two courses, one that combines python programming skills and HMIS data, and one that is focused on data analysis, visualization and sharing. I try to link these courses with my HISP Tanzania work promoting data use at different levels of the country, and I draw on these real-world use cases with my students.

A recent development in our subnational capacity strengthening work in Tanzania has been establishing the District of Excellence project in two districts in the Dodoma region, where we are specifically working on building capacity to enhance data use at the local level. In the past, we have found that there is typically little data use at the point where the service is provided and data is generated. We are trying to change that to help people make use of data locally, rather than waiting for analysis and action from the national level.

I have definitely seen positive changes in DHIS2 capacity over time. Right after we had deployed the system at a national scale in 2013-2014, our team would have to provide direct support for even minor issues like user account creation, for the entire country. Now, what we are seeing is that MoH teams are able to do things like user management and data analysis in DHIS2 themselves. The MoH team has an HMIS WhatsApp group where all the HMIS people in the country participate. We see MoH teams doing things like identifying data quality issues and sharing them for discussion themselves. This is not something they could have done back in 2014, 2015 or 2016. So we have seen that there has been a clear increase in MoH capacity at the national level, while there are still some gaps at the subnational level.

How have you supported local innovation and adaptation to new challenges and needs?

As I mentioned earlier, we have seen that there is a challenge of data use. 10 years ago, the challenge was there was no data, and decisions were made based on assumptions. Thanks to DHIS2, we now have a massive amount of data, and the questions are more about the quality of the data and how it can be used. So, we are working on how to address these challenges, such as through capacity building and the District of Excellence project.

We have also seen the problem of data being held in closed DHIS2 instances, which are not accessible to all stakeholders, so we are trying to find ways to make this data visible. One approach has been through public portals. Tanzania is one of the few countries that publish MoH data in an HMIS portal, which is available publicly online and updated with data from DHIS2 every quarter: https://hmisportal.moh.go.tz/hmisportal/

However, we also know that not everyone is able to easily access data on the portal webpage, so we wanted to find a way to get the data directly to people’s smartphones, so that they can have the data right in their hands. WhatsApp is one of the most popular applications in Tanzania, so we designed an Analytics Messenger application where we generate information from DHIS2 and send it out to users via WhatsApp. This is one of our solutions for getting information to DHIS2 users as easily as possible. This application won the DHIS2 App Competition last year. We have shared it with other HISP groups so that they can explore using it in their use cases. Once we have incorporated their feedback into a stable and generic version, we will publish it on the App Hub so the community can use it too.

How do you engage with the DHIS2 core team, the HISP network, and the larger DHIS2 community?

HISP Tanzania’s engagement with the core team started way back with our initial deployment of DHIS2. Two members of the UiO DHIS2 team came to stay and work with us: Ola Titlestad was in Zanzibar for around a year, and Lars Øverland was in mainland Tanzania for around 6 months. They were both supporting us in the implementation and using our experiences here to improve the DHIS2 software. Since then, we have continued to work closely with UiO on DHIS2 requirements gathering, testing and feedback, and annual roadmap planning.

We participate in the DHIS2 Community of Practice, both responding to user questions and posting questions and updates ourselves. We work with other groups in the HISP network to host Academies, and support and mentor newer HISP groups in the region to help them grow and mature. Locally, we also collaborate with the UDSM DHIS2 Lab, which also provides technical assistance to the MoH. We also work closely with research group HISP Centre, including by exchanging PhD and Master’s students between Norway and Tanzania. Our students have gone to UiO to gain insights on information systems theory and experience with the global project, while students from Oslo have come to Tanzania to work with us and understand the DHIS2 platform implementation in a local context.

How would you describe your HISP group’s success and impact?

I would look at this from a few angles. On the one hand, the trust that more and more governments are giving us to support their DHIS2 systems over a long period of time is a good indication of our success within the HISP network. We started with MoH Tanzania, and are now working with ministries in effectively eight countries. Some of these countries are very difficult environments, but we have still managed to deploy resilient systems there. We saw this when Covid came. The systems shook, but they didn’t break.

Looking at the Tanzania mainland, we have supported the country for more than 10 years. Recently we published a documentary with the MoH telling this story. This shows how the national system in Tanzania has been robust enough, has been able to integrate with multiple programs and systems, and prosper throughout the years. Tanzania is a good example in the region of a stable HMIS that different partners and stakeholders work together to support.

A third angle is innovation. HISP Tanzania is agile and innovative. In addition to the Scorecard app, we have developed several innovative solutions that can meet both local and global needs. The fact that we have won the DHIS2 App Competition twice in a row indicates our maturity as a team, and shows our ability to translate local needs into solutions that work locally and can be applied globally.

It’s interesting to look back on where we are now and how we have evolved. When we started, we didn’t really think about all of these innovations. We needed a system that could manage the data and generate reports; that was the problem. Now, all these years down the line, we need innovative ways to visualize and analyze the data. The demands keep on changing, and as an organization and individuals we have evolved organically to see how we can stay on top of the game, making sure that we stay relevant to our stakeholders, and change proactively to address new gaps and challenges as they arise.

Learn more about how the HISP Centre and the HISP groups collaborate to support countries worldwide on the HISP network webpage.