Now is the time to invest in locally-owned health data systems

The current crisis in global health financing has revealed the success of long-term health system strengthening approaches that emphasize local capacity to use, maintain, and innovate with open-source tools.

The past two months have been a period of great upheaval in global health, driven in large part by the sudden decrease in health funding from the United States, and the abrupt end of programs previously funded by USAID and other U.S. government agencies. These cuts have had profound impacts worldwide, and the ensuing gaps in treatment, services, and disease surveillance activities—to name just a few affected areas—put local and global health at risk. According to Dr. John Kaseya, Director General of Africa CDC, individual countries depend on international aid for up to 80% of the costs of critical health programs like malaria and HIV. Africa CDC estimates that these cuts will result in 4 million extra deaths in Africa per year and put the world at risk of a new pandemic.

Health data systems have also been affected by these cuts. Platforms like PEPFAR’s global HIV database, DATIM, have effectively been turned off overnight, and local staff who supported data collection and analysis for USAID-funded programs have been furloughed or fired, creating immediate gaps in digital records that are used to coordinate life-saving treatment. However, there is a bright spot in this dark time: an informal survey carried out through the HISP network, which provides localized DHIS2 technical assistance in 90+ low- and middle-income countries, suggests that locally-owned national health information systems remain online, and ministries of health continue to use these systems to monitor public health and plan interventions. This is thanks to long-term investments in these systems and in strengthening the local capacity to use them effectively and to keep them running, and to their institutionalization within national health strategies.

The situation is fragile, however. Most low-income countries are still heavily dependent on external funding for their public health systems. Digital public goods (DPGs) like DHIS2, which are the foundation for the large majority of these routine health data systems, are also primarily supported by global health funders. While this crisis is accelerating the movement toward greater contributions from low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) to these costs—particularly in Africa, where “countries are advancing innovative frameworks to reform health financing”—this shift will take time, and additional gaps will arise without continued support. At a time when budgets for global health are tight, it is important to invest in effective and sustainable solutions. When it comes to health data, that means investing in routine data, open-source tools, and local system ownership.

Funding disruptions and impact on health information systems

Data systems are a small but integral part of national health systems, enabling countries to monitor population health, assess health risks, prioritize interventions, make budget decisions, and evaluate programs. Some countries also use digital tools to monitor individual patient health, coordinate follow-up care, and maintain unified electronic records.

While disruptions to these systems pose a less immediate threat than shutting down HIV treatment centers or stopping food distribution, the impact remains significant. Without access to this data, governments struggle to manage health programs effectively. This challenge is heightened as global health funding has declined since the end of the Covid pandemic, forcing low- and middle-income countries to operate with fewer resources (source).

Funding cuts in LMICs can lead to systems going offline or running at reduced capacity due to the loss of funds for essential costs like servers, internet, and software licenses. For example, in Kenya, the Ministry of Health suddenly lost access to the national Electronic Medical Records system in March (source). Staff reductions—whether government-funded or seconded from U.S. agencies like the CDC—can also disrupt data entry and use. In extreme cases, U.S.-funded parallel systems have been shut down entirely. Over time, persistent funding gaps can mean that systems are less able to adapt to changing needs, such as the introduction of a new vaccine in an immunization program, or to make software updates that introduce improved features or fixes for new security vulnerabilities.

There have been a few attempts to measure the impact of the recent funding disruptions on health information systems in LMICs. The WHO-led Global Strategy on Digital Health Secretariat has launched a survey on the Impact of Reduced Support on Digital and Data Systems for Health, but the results have not yet been published. A rapid survey carried out in February 2025 by the Health Data Collaborative collected 79 responses from 37 countries. The results showed that only 33.3% of the systems reported were still “fully operational,” and that data management and reporting had been disrupted in 69.7% of them. However, 90% of respondents were non-governmental bodies, and only 10% were governmental agencies, making it difficult to draw conclusions from this survey on the current status of national health information systems.

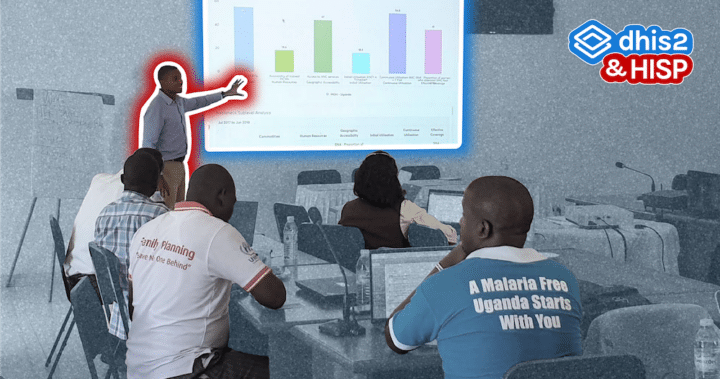

Surveying national health information system status through the HISP network

At the HISP Centre at the University of Oslo (HISP UiO), our team develops and maintains the open-source DHIS2 software platform, which is used by ministries of health in more than 90 countries in the global south as an integrated health information system (HIS), with 75 of these countries using DHIS2 at national scale. DHIS2 thus serves as the backbone for routine data collection on public health programs that touch more than 40% of the world’s population—roughly 3.2 billion people. HISP UiO also coordinates the HISP network, which is made up of 23 local HISP groups based in countries in Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and Latin America. For more than a decade, these groups have worked with national, regional, and international partners to support the set up and operation of national DHIS2 systems in most of the 90+ countries where DHIS2 is used, as well as helping to strengthen the local teams within ministries of health to take direct ownership of these systems.

When the news of the U.S. funding cuts broke, it was imperative for HISP UiO to get a rapid overview of the impacts on national DHIS2 systems, so that we could identify any critical gaps and work with local and global partners to keep these essential systems online, including advocating for additional resources if needed. We carried out an informal survey across the HISP network to document system status per country. The responses revealed an interesting insight: while many project-funded or program-focused systems have been shut down, and while we have identified some disruptions in individual DHIS2 systems due to partial reliance on U.S. funding or seconded personnel, the trend we are seeing is that all national HIS systems remain online, supported by local staff, and that routine data collection and analysis continue, though with some disruptions and impending gaps depending on the local funding and staffing structures.

This finding supports central parts of the vision that has guided the HISP network since its beginnings: The key to building resilient, sustainable, and effective health information systems is to focus on routine data that serves the needs of country stakeholders—not just international donors—and to strengthen capacity for local ownership of these systems and the data they contain.

“Uganda has successfully utilized DHIS2 to enhance health data management and accountability, supporting case-based analytics for TB, immunization, and COVID-19 vaccination certification. The system has also been integrated with ICD-11 for improved death notification and certification. The Ministry of Health leverages DHIS2’s powerful visualization engine for better data accessibility, while HISP Uganda provides capacity building and backup support. Despite recent budget cuts, DHIS2 implementations have remained resilient, continuing to deliver critical health data and support decision-making. Uganda’s experience highlights DHIS2 as a transformative tool for sustainable health information management and service delivery.”

— Paul Mbaka, Assistant Commissioner, Division of Health Informatics, Ministry of Health Uganda

Routine data systems are more resilient than parallel systems

When people think about digital health, particularly in the global north, they may imagine smartwatches, remote sensors, or electronic medical records (EMRs). There has been tremendous innovation aimed at personal healthcare and at providing new tools for doctors and clinicians. Despite these advancements, the cornerstone of public health is focused on the population, rather than the individual. Surveillance systems and regular statistics are essential for pandemic prevention, tracking health trends, measuring progress toward Sustainable Development Goals, and managing medicine procurement.

DHIS2 plays a fundamental role in most LMICs as an integrated national HIS–the system of record that is used to collect data from health facilities on service delivery and health outcomes for all fundamental health programs, such as maternal and child health, immunization, HIV, malaria, tuberculosis, and more. Depending on the available digital infrastructure in a specific country or region, this can include basic individual health records in DHIS2 that cover a variety of health services provided in primary care. But in all countries, the foundation of the HIS is routine aggregated data reported by health facilities on a regular basis, such as daily, weekly, or monthly. This data can be entered by health facilities directly into the DHIS2 system, or filed as paper reports that are entered at the district level. Such aggregated reporting systems are the cornerstone of public health monitoring and programming, and have decades of demonstrated sustainability. They require smaller investments to scale and maintain than patient-facing systems, making them practical, reliable solutions for ensuring that crucial health data are captured and reported in low-resource settings. This aligns with growing calls for “low-tech” approaches to innovation that focus on “locally affordable, efficient technologies” as a way to ensure that they are “sustainable, accessible, responsible and ethical” (source).

The potential of such “low-tech” systems should not be underestimated. These national health information systems have had a real, positive impact on health programs in LMICs. In Ethiopia, for example, the Ministry of Health has scaled its DHIS2-based HIS nationwide, achieving more timely access to more complete data, which has supported more efficient planning and timely decision making (source), and recent research has found that DHIS2 reporting at facility level correlates with improved patient satisfaction (source). In Kenya, the national DHIS2 system has helped “improv(e) data accessibility and communication between health facilities” and “contributed to more coordinated and efficient healthcare service delivery,” while the the real-time data collection and analysis provided by the system “have improved the accountability and openness of health systems, reducing errors, enhancing treatment results, and facilitating evidence-based policymaking” (source). In Bangladesh, which operates the largest national DHIS2 system in the world, digitalization of its national HIS has improved decision making (source). In Nigeria, combining routine immunization and vaccine supply-chain data in DHIS2 has helped reduce stock outs and improve immunization coverage (source). And in Somalia, DHIS2 is used to support the government’s universal health coverage goals by “calculat(ing) a range of key performance indicators that monitor trends in outputs, use, and coverage” (source).

In addition to supporting the routine operation of health programs, these open-source systems provide countries with a flexible digital platform, supported by local teams, that they can quickly and easily adapt to help respond to emerging threats without needing to purchase new software or hire external consultants. This was clearly demonstrated during the Covid pandemic, where 59 countries used DHIS2 to help manage their national response, including disease surveillance, test result management and certification, and vaccine delivery. In many cases, LMICs were able to adapt their existing DHIS2 systems to integrate Covid-related programs in a matter of weeks or days (source). More recent examples have included Rwanda’s use of DHIS2 to manage the response to the 2024 Marburg virus outbreak (source) and Uganda’s successful control of its Ebola outbreaks (source). Investing in these kinds of routine digital systems built on flexible technology, and building the capacity of local teams to operate and maintain them, ultimately makes LMIC health systems better equipped to respond to crises.

“At the Family Health Bureau, we continue to rely on DHIS2-based health information systems to support evidence-based decision-making in maternal and child health. These systems function as fully government-funded platforms, ensuring long-term sustainability. With strong national ownership, we have been able to maintain and strengthen data collection, analysis, and use, ultimately improving the quality of care for mothers and children in Sri Lanka. Availability of local capacity and access to the regional and global DHIS2 community boost our confidence in expanding DHIS2 implementations for our requirements.”

— Dr. Kaushalya Kasturiaratchi, Head of Monitoring and Evaluation Unit, Family Health Bureau, Ministry of Health, Sri Lanka

Invest in what works and what lasts

Long-term investments in strengthening routine health information systems, and the open-source technologies that support them, have resulted in positive impacts on health programs in low- and middle-income countries, helping them make progress toward Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3 by providing timely data to inform better decisions. In addition, by supporting local ownership and local capacity, these investments have enabled these systems to continue operating through the current global health funding crisis. This is the model that HISP has promoted for more than 30 years, and which DHIS2 is expressly designed to support.

Of course, funding for national health systems is complex, and the specifics of how systems and staffing are funded varies by country. While our informal survey indicates that all DHIS2-based national health information systems are still operational, there are some systems facing more acute gaps than others. Isolated examples we have uncovered include data collection being halted for certain programs (such as TB) where local staff was being paid from U.S. project funds, or core DHIS2 technical teams that were funded entirely by U.S. agencies being furloughed. The HISP network is working with national and global partners on solutions to these issues, including providing stopgap technical assistance where needed. Ultimately, the sustainable solution is greater institutionalization, through a continued emphasis on–and investment in–health system strengthening, including data and digital infrastructure.

With the sudden decrease in health funding, organizations have pointed to the opportunity to focus on DPGs as sustainable, adaptable tools that countries can scale and innovate on. In a recent post on ICTWorks, Maeve de France and Martin Noblecourt of CartONG noted that for humanitarian data, where organizations are now forced to “do more with less,” this crisis could be an opportunity to “refocus on essential” and leverage existing resources from the “digital commons.” These resources and software tools already “benefit from shared resources from other sectors who also use them” and present a “clear path to scale.” They conclude that “sustaining support for key digital commons and data products is crucial.”

No one expects—or necessarily wants—health financing in LMICs to be donor-funded forever. A recent article in DevEx noted “unexpected tones of optimism” among participants at the Africa Health Agenda International Conference in Kigali, Rwanda, in early March, as some participants felt that “the continent could be at a crossroads moment where it could change the existing paradigm towards reimagined health systems that are more integrated, with genuine ownership by African governments, and are buoyed by more sustainable financing.” This vision is also supported by the Lusaka Agenda, which calls for a sustainable transition from global health funding to domestic public financing of health programs.

This also applies to funding for digital public goods like DHIS2. While many DPGs, including DHIS2, are free for LMICs to use, they are not free to develop or maintain. The work of HISP UiO has largely been funded centrally through grants and contracts with global health institutions and development agencies, and we are working to shift our funding model toward country-level contributions, to make the costs of our open-source platform visible in national budgets. We think this will support greater sustainability of our project, and increase ownership of our platform in the global south.

However, these changes will not happen overnight. The Financing Global Health 2023 report found that global health funding to LMICs had decreased from the peak of the Covid years, and was likely to return to pre-pandemic levels or decrease, meaning that countries were already facing a more limited financial environment even before the U.S. funding cuts. The authors found that government spending on health in LMICs was “far lower than what is needed to provide adequate health care.” However, given limited available resources in LMICs, shifting to local health financing will take time. “Funding for global health,” they wrote, “remains as urgent as ever.”

This statement is even more true now. We have only seen the immediate effects of the sudden cuts to U.S. health funding so far. The larger, long-term effects, such as the impact on the budgets of global health funding institutions like Gavi and the Global Fund, and thus on the programs they support, remain to be seen. Thankfully, donors and aid agencies around the world are already stepping up to help fill gaps and keep vital health programs running. As far as health data is concerned, in a time when budgets are tight and there is a need to focus on essentials, our message is to invest in what works and what lasts: locally owned routine information systems, the digital public goods they are built on, and the local capacity to keep them running. This will ensure that these systems remain resilient and adaptable, helping low- and middle-income countries meet health needs and respond to challenges in the years to come.

Learn more about our work and opportunities to partner with us: